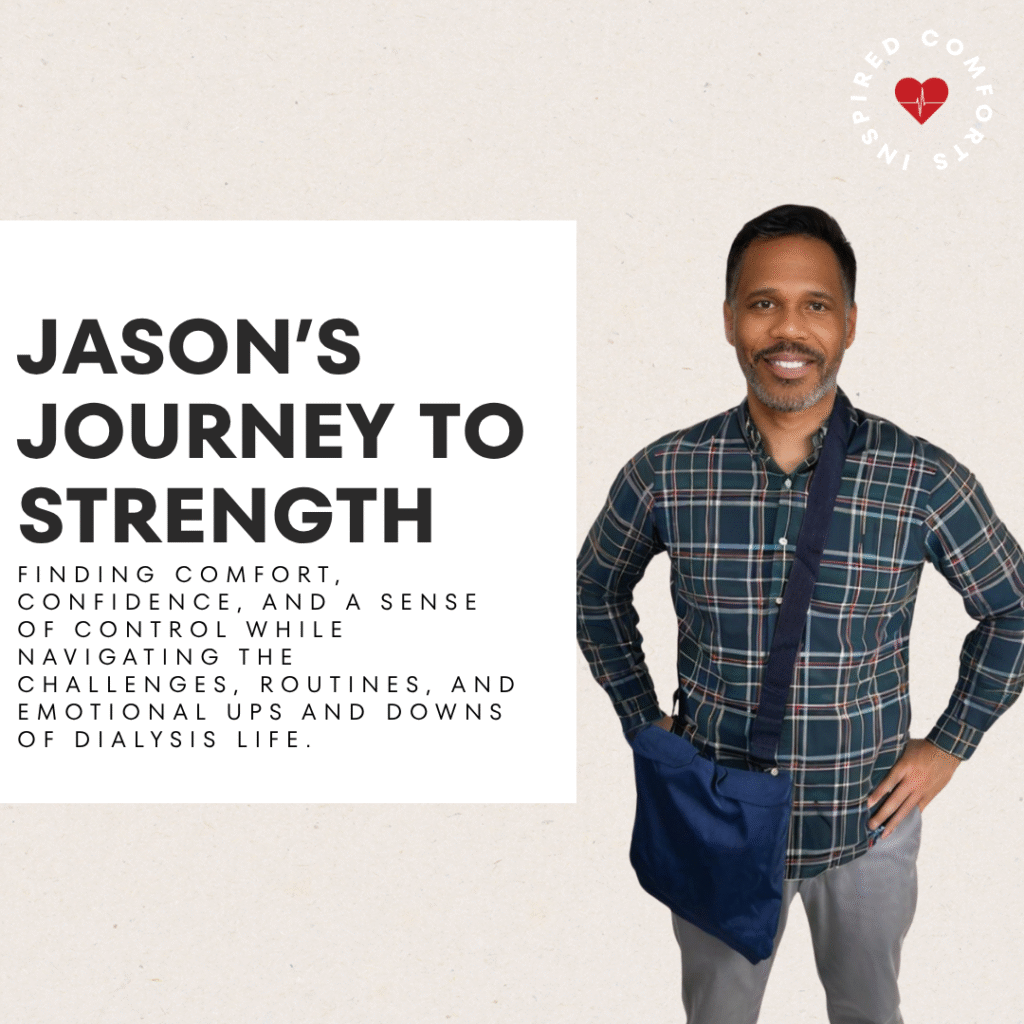

At 42, Jason Miller never imagined life would pause like this. He had always been the one people leaned on. A big brother, a provider, a father figure to his younger cousins. The kind of man who worked long hours, skipped checkups, and smiled through back pain, thinking it was all just part of being strong.

But one morning, he couldn’t get out of bed. His legs were swollen, his breath came in short gasps, and everything felt heavy. At first, he thought it was just exhaustion. Until the emergency room visit turned into a hospital stay. That was the day he learned his kidneys were failing.

“I did not even know what dialysis really meant,” Jason says, sitting in a soft chair by the window of his apartment, where he now spends most of his days resting between treatments. “They said both kidneys were gone. Just like that. Gone. I kept asking them, what did I do wrong?”

The truth is, chronic kidney disease often shows no clear symptoms until it is already advanced. In Jason’s case, it had been silently progressing for years. Now, his survival depended on a machine.

Three times a week, Jason is hooked up to a dialysis machine that filters his blood because his kidneys can no longer do the job. Each session lasts nearly four hours. Four hours of needles, monitors, and the whirring sound of a machine that now stands between him and the life he used to know.

Dialysis is not just a treatment. It becomes a rhythm that dictates your days. It brings fatigue that no nap can fix. It brings cramps and nausea that come without warning. It makes planning life difficult. For Jason, it also brought isolation.

“People stopped calling. Not because they did not care, but because they did not understand,” he says. “You tell someone you are on dialysis, and they go quiet. It makes you feel like you are already halfway gone.”

There were days he wanted to give up. Days he sat in the dialysis center watching the clock, feeling like time was a cruel joke. But something kept him going. His daughter.

She is ten. A curious, giggly child with a love for science and a habit of leaving sticky notes on the fridge with messages like “You are the best, Dad.”

“She asked me once if dialysis was making me better. I told her it was helping me stay here with her while we wait for something better to come,” Jason shares, his voice catching slightly. “I think that was the moment I stopped feeling sorry for myself.”

Now, Jason is officially on the transplant list. He checks his phone every day, hoping for the call that could change everything. The wait can be long. Sometimes years. But he holds on to the belief that someone, somewhere, will say yes to giving him a second chance.

“People think healing always means getting back to who you were,” he says. “But for me, healing means learning how to live again, even when life does not look the same.”

Jason has started journaling. He attends a support group for other dialysis patients and recently began sharing his story on social media. He talks about the importance of routine, hydration, mental health, and asking for help. He also speaks openly about fear, about grief, and about the guilt that sometimes comes with receiving help from others.

“There is a kind of courage in letting people see your pain,” he says. “We do not heal in silence. We heal when we are seen.”

As the sun sets behind him, casting soft gold across the dialysis machine by the corner, Jason leans back and says, “I am still here. Still waiting. Still hopeful. And for now, that is enough.”